Constructive Programme: Its Meaning and Place

by M. K. Gandhi

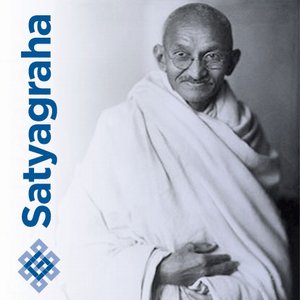

Editor’s Preface: We are presenting here the full text of Gandhi’s Constructive Programme: Its Meaning and Place, published on March 11, 1941 (Ahmedabad: Navajivan Publishing House). Although for decades he had been airing these views, this last version consolidated his ideas into something of a manifesto that, he hoped, would shape the campaigns and purpose of his later years. Gandhi conceived of satyagraha as having two branches, the Constructive Programme and nonviolent Civil Disobedience, and after decades of civil resistance campaigns had increasingly turned his attention to social action, local community development, self-improvement schemes, education and the like, which he attempts to codify here. Although this pamphlet was written and published near the end of his life, Gandhi had already articulated these views, as early as his South African campaigns, and before his return to India in 1918. The Constructive Programme also had a profound influence on the post-Gandhian, Indian nonviolent movement, now referred to, somewhat misleadingly, as the Sarvodaya Movement, although it was many movements interpreting Gandhi in diverse ways. See also the textual note at the end of the article, for further bibliographical information. JG

Introduction

The constructive programme may otherwise and more fittingly be called construction of Poorna Swaraj or Complete Independence by truthful and nonviolent means. (1) Efforts for the construction of Independence so called through violent and, therefore, necessarily untruthful means we know only too painfully. Look at the daily destruction of property, life, and truth in the present war.

Complete Independence through truth and nonviolence means the independence of every unit, be it the humblest of the nation, without distinction of race, colour or creed. This independence is never exclusive. It is, therefore, wholly compatible with interdependence within or without. Practice will always fall short of theory even as the drawn line falls short of the theoretical line of Euclid. Therefore, complete Independence will be complete only to the extent of our approach in practice to truth and nonviolence.

Let the reader mentally plan out the whole of the constructive programme, and he will agree with me that, if it could be successfully worked out, the end of it would be the Independence we want. Has not the Colonial Secretary Leo Amery said that any agreement between the major parties will be respected? We need not question his sincerity, for, if such unity is honestly, i.e., nonviolently, attained, it will in itself contain the power to compel acceptance of the agreed demand.

On the other hand there is no such thing as an imaginary or even perfect definition of Independence through violence. For it presupposes only ascendancy of that party of the nation which makes the most effective use of violence. In it perfect equality, economic or otherwise, is inconceivable.